Interview: Graham Dickie

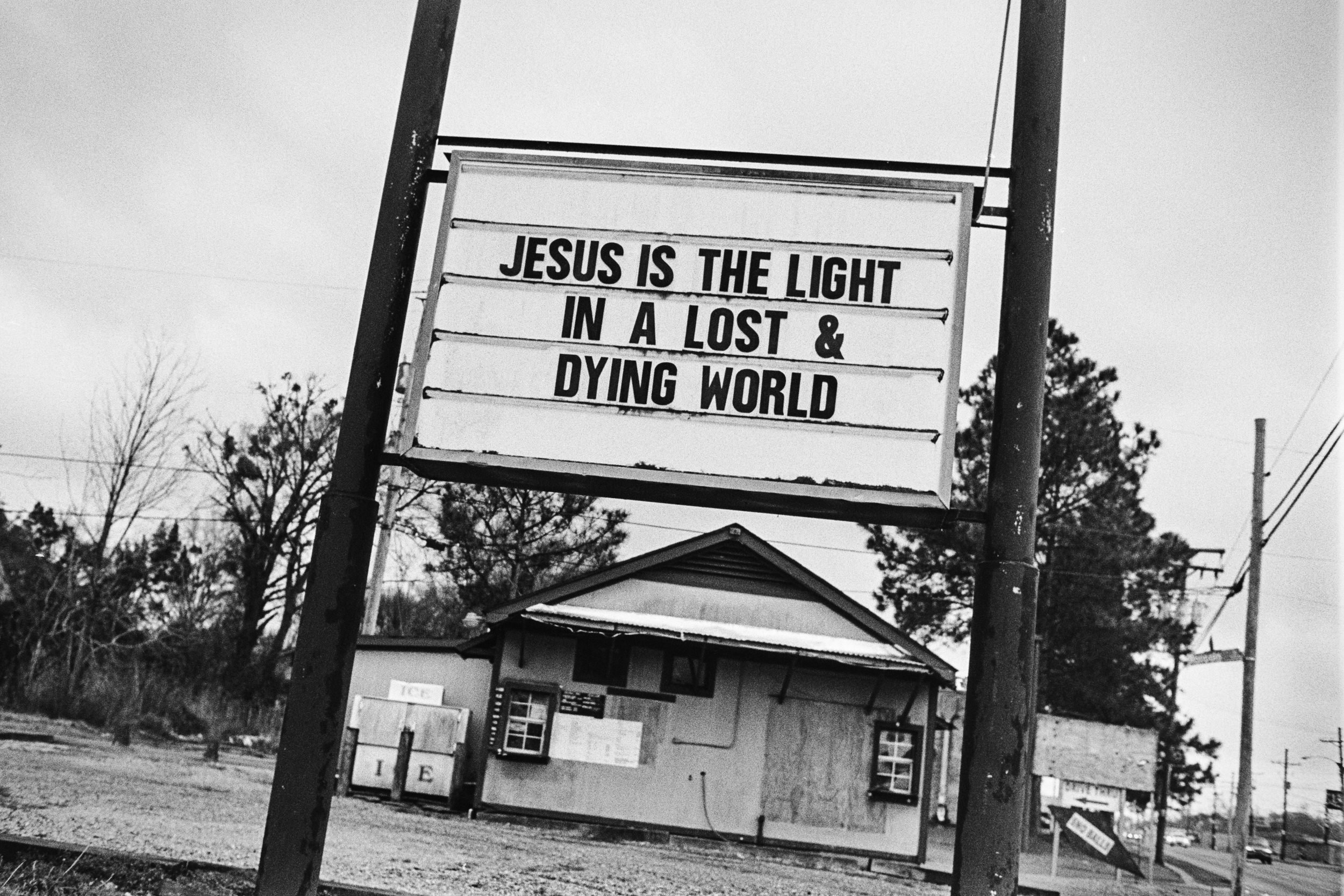

With the support of the Film Photo Award, Graham has continued a long term project to photograph rap and daily life in Louisiana, paying particular attention to the countryside surrounding Baton Rouge. “How Life Is” approaches the state's street rap scene with a grass roots, humanistic perspective, focusing on young aspiring artists and how their music, with its deeply autobiographical underpinnings, connects to their communities and speaks to America's broader reckoning over racial injustice.

In 2022 photographer Jared Ragland caught up with Dickie while on a stop during an epic hike down the Continental Divide. The following interview is edited for brevity and clarity.

© Graham Dickie

Jared Ragland: It sounds like this hike is quite different than the work that you've been pursuing in Louisiana. What was the impetus for the hike? Are you photographing?

Graham Dickie: I’m on the Continental Divide Trail, which is more of a route than a trail per se, because it basically stitches together 3000 miles of dirt road, old railroad grade, faint mining trails, or just no trail at all, from Canada and Mexico. I began walking it as a means of looking for something different, to make me think differently. I haven't been carrying a “real camera” on the trail––I've just been using my phone. I think this is the longest period I’ve experienced without picking up a proper camera, so I'm starting to get antsy and really excited about photographing again when I get home. But for now, there's a kind of a monastic quality that I have enjoyed about the hike––to just have everything I need on my back. I’ve found a great way to see the country, as well.

JR: How does this journey connect to the Louisiana work, or does it?

GD: I felt like I had reached that point with the Louisiana work where, you know, it's always hard to know when a project is over, but I feel like there's a lot of work there, and I'm pretty happy with it. This hike felt like a way to turn the page, clear my head, and then reassess once I’m back home in Austin.

JR: That’s an interesting idea––the monastic experience––and using this time as a means of perhaps contending with who you are, where you've been, what you're doing, what you’ve made. History and literature are full of stories about young men on the road who come to some sort of conversion or means of self-discovery. Have you come to any new realizations or had any “ah-ha” moments as you're walking?

GD: Just before I left on this trip one of my good friends in Louisiana who I'd met through photographing, died. He was a pillar of my work there. His name is Delta, and he was killed in a shooting. Just before I came out West I went to his funeral, and I've been thinking about him a lot. He'll pop into my head at random times on the trail, while I’m walking through a meadow or something, and when I think about what the work in Louisiana has given me, a lot of it comes back to having personal connections. To have had Delta in my life, and to have somebody that I considered a real friend, makes me miss him a lot and feel grateful for the people I've met that are still around. So that's been a big takeaway and probably the thing I've been thinking about the most. Delta’s death is another reason why I felt the project was coming to a close. I’m still connected with his family, but things don’t feel the same without him.

What it always comes back to, for me, is using photography as a tool for creating connection and finding meaning. Now that I’ve been out here now by myself for three months, I yearn for that connection even more. So it'll be interesting to see once I’m off the trail how I will use a camera.

JR: Thinking about photography as a tool for making connections and building community--can you tell me about how you build and foster relationships with the people that you photograph?

GD: I was really lucky to have an apprenticed with Danish photographer Jacob Aue Sobol right after I finished university. Being with him and absorbing his philosophy shaped a lot of how I think. One thing I remember him saying is, “take the camera out of the equation when you're approaching people, when you're conceiving of an idea––just make it about your connection with that person, then let the photography come after that.”

JR: So intuition is playing a big role in making connections…

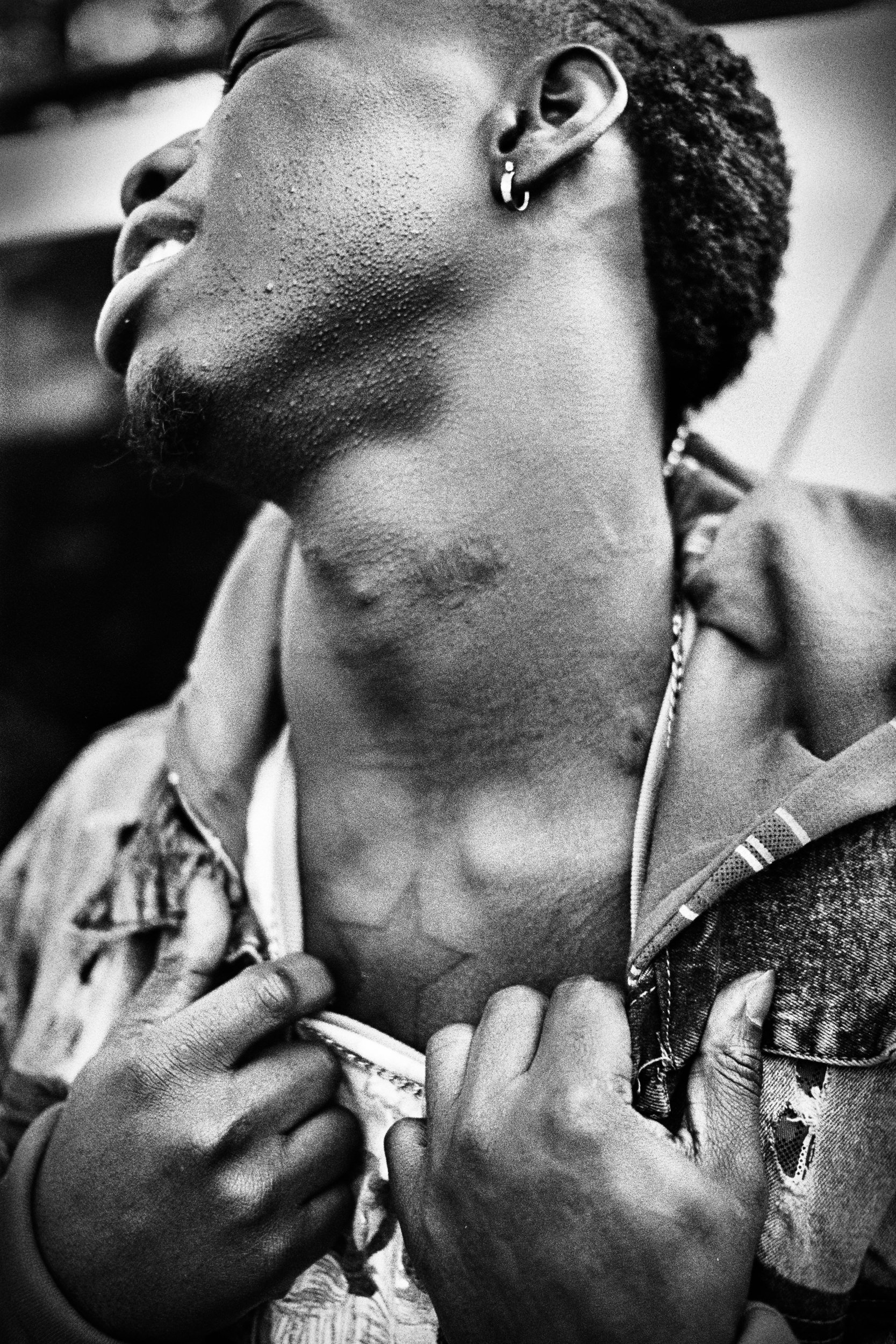

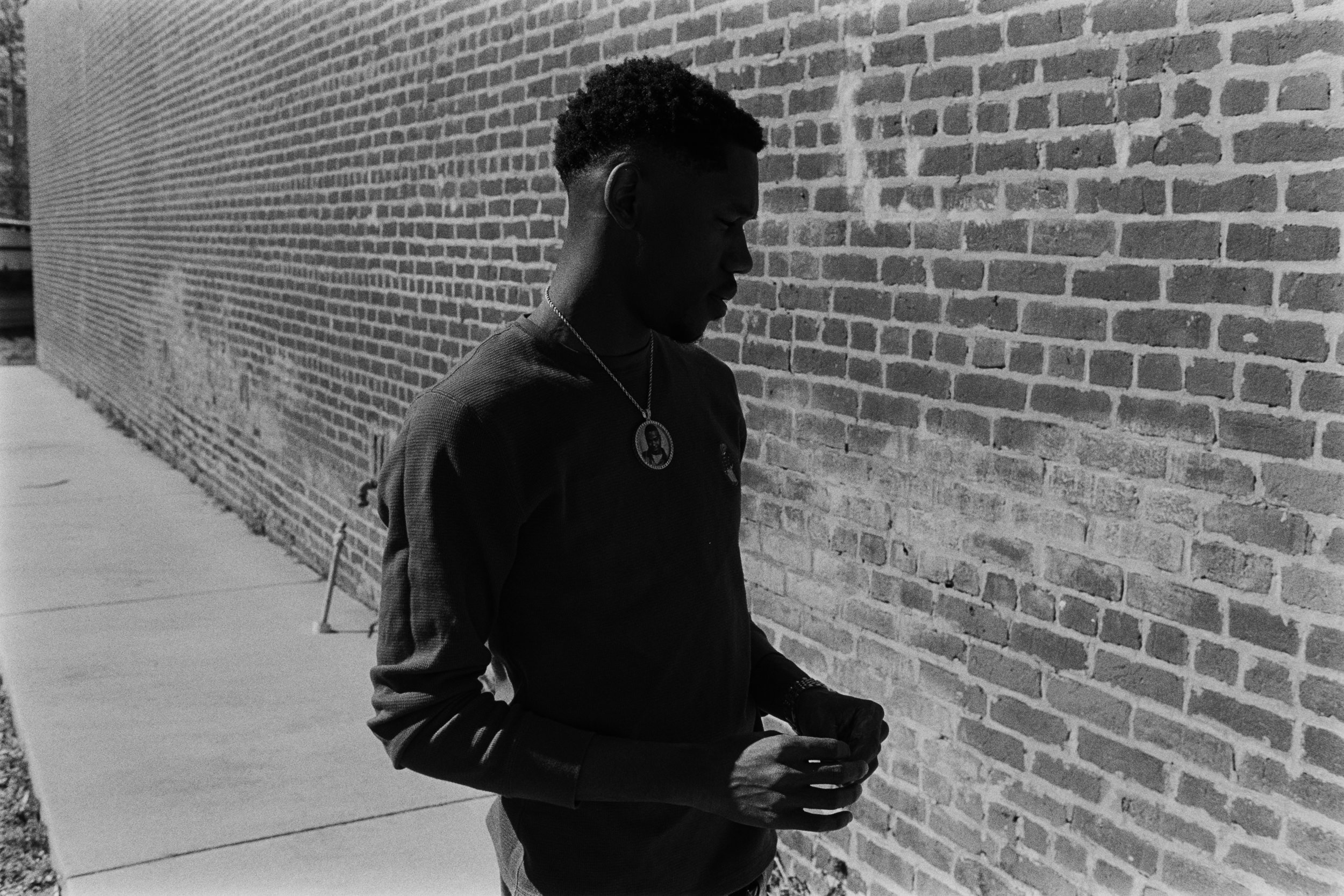

Jay. Jackson, Louisiana.

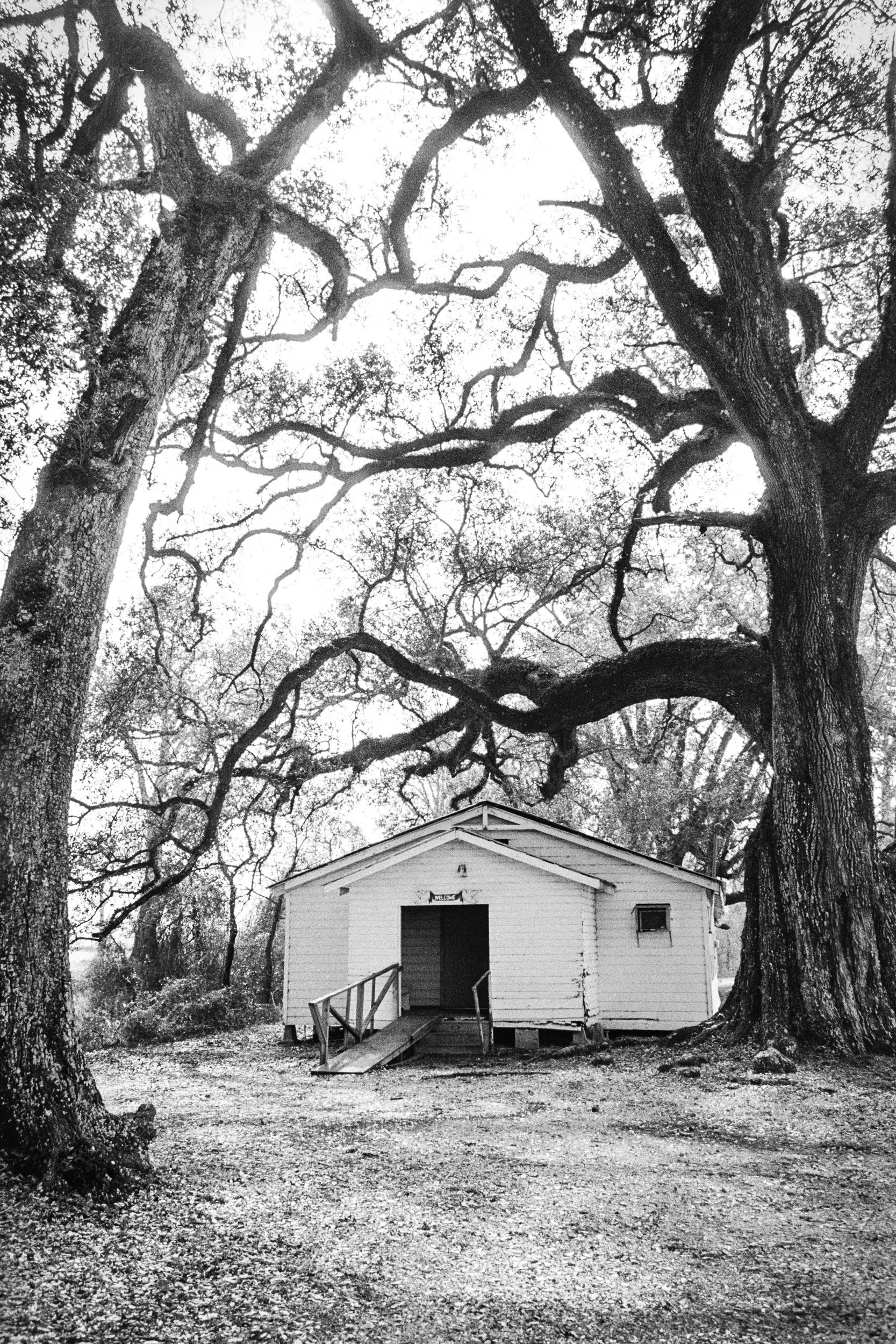

Maringouin, Louisiana.

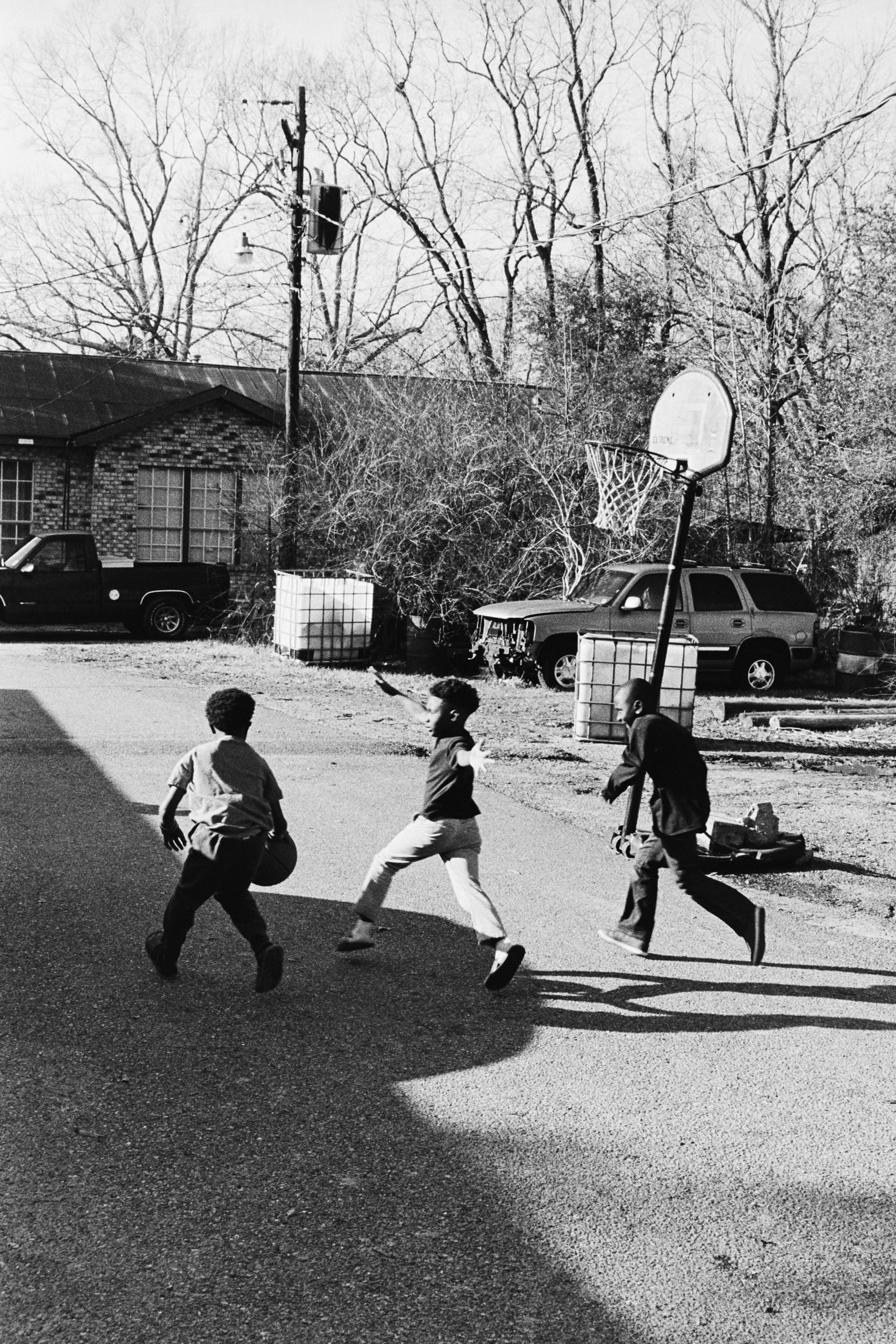

Roseland, Louisiana.

GD: Yeah, definitely. I think as photographers when we are out photographing we often know in our gut, or through impulse or intuition, that we connect with certain people. We may not know how or why, but we definitely feel it. I think using that impulse as a driving force towards who I approach and how I approach them makes a world of difference. It’s not about stopping every random stranger to take a portrait; it’s about practicing a deeper thoughtfulness by asking, “what is it about this person and how can I connect with them and get to know who they are?”

JR: Tell me about the connections you’ve made in Louisiana.

GD: I've photographed tons and tons of people in Louisiana, but there are pillars––people like Delta that I’ve been able to build relationships with. That’s what's so interesting to me about photography: it uncovers, it reveals, it connects. I often wonder why am I drawn to this place, or this object, or these people? And I think, ultimately, the important thing is just that I am, and I want to honor that by coming to it from an authentic place and place of respect with people.

Club Bella Noche. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

JR: Your project “The Old Man on Blank Street” is borne out of the same mixture of instinct, happenstance, and authentic connection, right?

GD: Yeah, Richard is a good friend now, but at the time, he was just the guy I met on the street. He was walking his dog one morning, and I was photographing his house––he lives in one of those old southern neoclassical houses––and he saw me and invited me in for tea. Richard crystallized something about the way photography can bring people together. Both of us were looking for a connection and decided to see how far that can go.

JR: It's interesting to consider how these two projects, “How Life Is” and “The Old Man on Blank Street” have as much to do with the creation and interpretation of place as they do with portraiture. What role does place play in your work?

GD: For the first trip I did for “How Life Is” I went all over the South. From Austin I did a circuit to Houston, then to Baton Rouge and New Orleans then up to Huntsville, Alabama and Jackson, Mississippi and a handful other places, but there was just a real palpable energy in Baton Rouge and its countryside that grabbed me. I was looking at your work, and you talk a lot about the intensity of Southern history and all that’s beneath the surface––it's hard to not to imagine not photographing there, because I haven't found anywhere else like it.

Jackson, Louisiana.

JR: There’s definitely a unique relationship between ideas of “place” and the rural South. I think about the work of Clarence John Laughlin or Debbie Fleming Caffery, who both have worked from hybrid documentary/surrealist approaches in southeast Louisiana––Loughlin being more surrealist and Caffrey more documentary––but both still getting to the essence of the place. I find your work fitting in line with that kind of hybrid type of making: authentic yet dreamlike, documentary yet expressive. Who have been some of your photographic touchstones?

GD: A model for me, more than the photography that’s been made there, is the music of Louisiana. I’ve always been super drawn to it. Because, I mean, THE SOUND. The people are always listening to local music, and there's always something new. It's always in the air, and somehow it’s the perfect complement to the texture of daily life. If you're just driving around and listening to NBA YoungBoy or Boosie it just feels like it emerged from there; it really is the soundtrack to the place. So the music, more than anything, was always an inspiration for me, as well as a challenge to capture a sense of it and channel it somehow through the images.

But photographically speaking, I have always been influenced by the traditional documentary style. I’ve always admired Wayne Miller, who did great projects in Chicago’s Southside in the 40’s and 50’s, as well as Alex Webb’s early stuff from the Mississippi Delta.

Delta rapping a new song. Jackson, Louisiana.

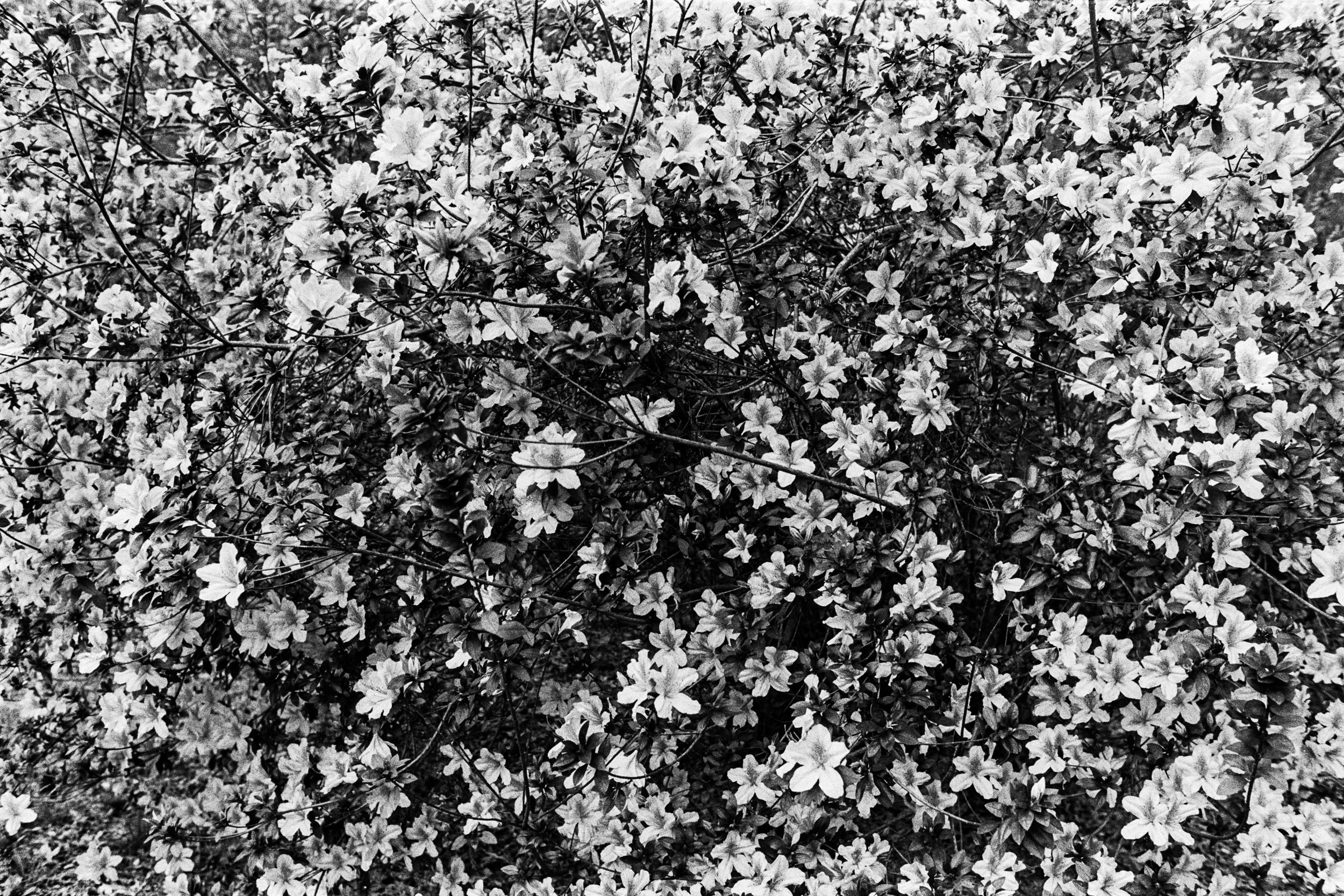

Deer Creek. Zachary, Louisiana.

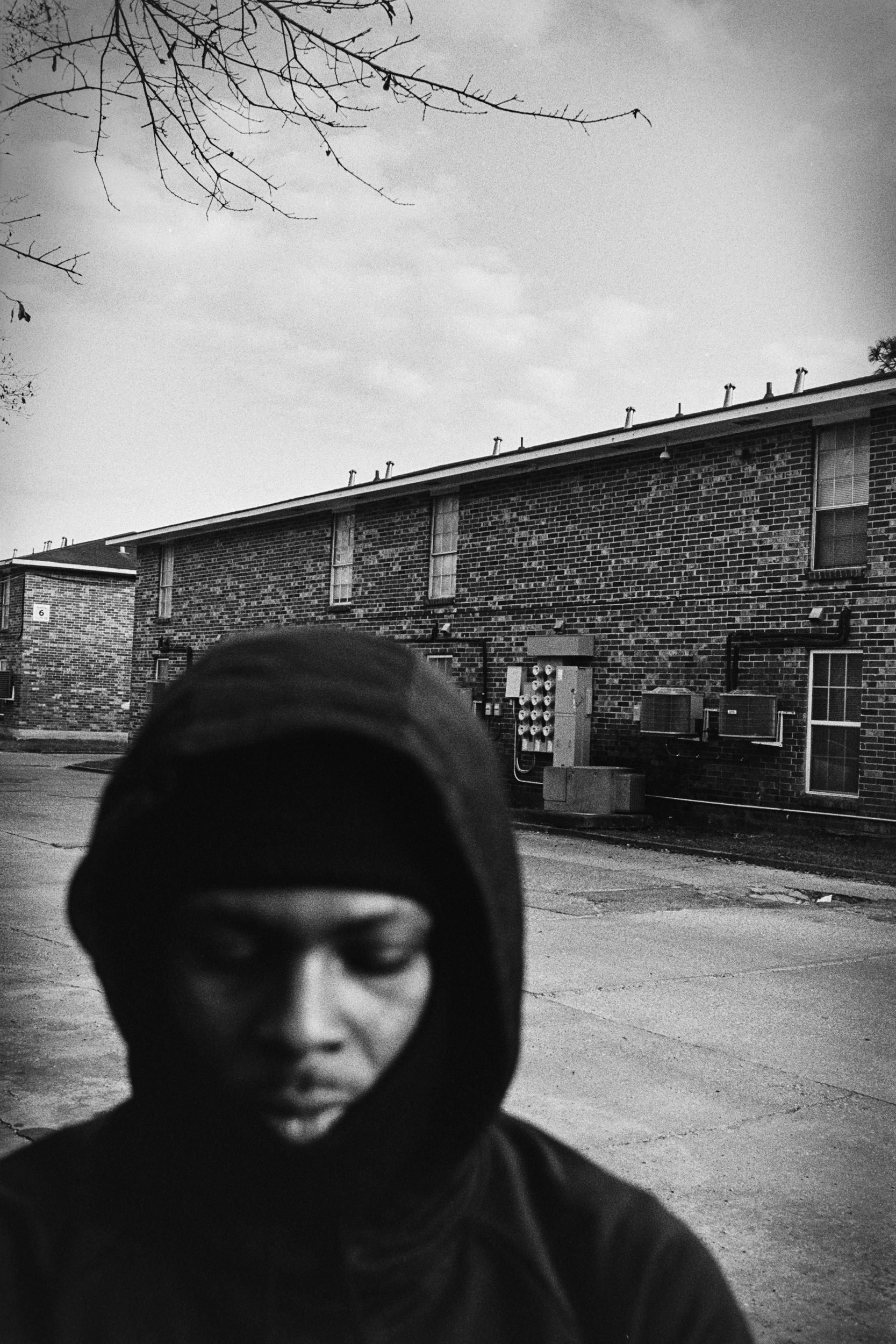

Mohican Street. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

OG Shaggy at 4 Feva's studio. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

JR: That's really interesting––pairing the idea of musical thinking and creating photographs. You mentioned Eli Reed’s pictures as having a sense of grace, which makes me think of harmony and connection. How do you “harmonize” with–and I mean that metaphorically–the people you photograph with? How do you find the grace in picture making?

GD: I think being as present as possible is important, and also making myself vulnerable and just taking part in life a really big thing. For a while I was bound by the idea of journalistic distance, but once I started to let that go Baton Rouge became my home away from home, and the people I was photographing became my friends. Together we formed really meaningful and authentic connections––which changed my life and the way I look at the world––and I just wanted to bring that into the way I was photographing.

Jackson, Louisiana.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Early on my pictures followed that more formal documentary approach, and then I went to work for Jacob aue Sobol. Under Jacob the work became more expressive, and the longer I stayed with it the more willing I became to make it personal, to follow impulse, and make room for the irrational. I let go of the preconceptions of what I needed to get or where I needed to go and instead would just hang out and make pictures. And then at the end of every day I would make prints and gradually puzzle everything together, following things as they came. In that way, the work took on a sort of musical way thinking.The musicians in Louisiana taught me a ton about photography, just by watching them in the studio and then seeing and hearing what music came out of it. Something I've always admired about Louisiana rap is its visceral quality. I remember being with Tweezy Bandoe and BBG Tyler, and I remember Tyler saying, “You know, people in Baton Rouge, we don't go to the studio for some sort of intellectual exercise of, like, who can make the most complicated rhyme––we just want to throw something out from the stomach, from the gut.” And that’s always had an appeal for me. It's a gut punch. A lot of the art I admire from the South has that same quality to it, whether it's a story by Carson McCullers, or older Blues music, or stuff by NBA Youngboy today. I just feel like there's something there that's not premeditated and instead comes from the heart.

JR: I certainly believe that intuition is paramount in our work as documentarians. It’s also interesting to think about how working in that way is a form of improvisation, much like making music.

GD: When I was editing my selects for the Film Photo Award, it was like that. It's so exciting to not have any expectations for a concrete narrative, but to then create a story in a sort of rapid, almost freestyle form. You can know immediately if something doesn't work, when a picture is like a bad note––it just doesn't sound right. But you also know when it sounds right, too. And that is one of the most satisfying things about sticking with photography over time. As I continue to do it, I feel more and more confident in my decision making and ability to find the core of the project and let it emerge and build in a kind of magical way.

JR: So since it's the Film Photo Award, perhaps we should talk about film. How has the process of using analog film informed the pictures?

JR: There's a hint of Dennis Darling in there, too, maybe? Did you study under Dennis at UT?

GD: I actually studied with Eli Reed, and he was for sure a big influence.

JR: Oh, yeah, of course. How did working with Reed influence your practice?

GD: He was one of my thesis advisors, and without Eli's influence I don’t know where I’d be. He's an amazingly supportive and inspiring person. Just hearing him talk––everything he said was a nugget of sage wisdom. He's someone who comes from that classical documentary tradition. There’s just so much grace in his pictures.

Roseland, Louisiana.

Roseland, Louisiana.

Clinton, Louisiana.

GD: I've toggled back and forth between film and digital. Some trips I've only shot film, other trips I've only done digital, and then sometimes I've done a mix. I always feel like film encourages something a little bit more spontaneous and unmeditated and sort of playful, almost because you can't look at it, you don't know exactly what it's going to be, and you have a limited number. I like that quality of it, and the moments are just more precious. With a digital camera I might take 20 frames that are really similar to get the composition just right. But with film I have to embrace the imperfection and casual quality that photographing with a 35 millimeter brings.

Norwood, Louisiana.

While I was shooting in Louisiana I would develop the film at the end of every day. I'd be staying at my friend's old Victorian-era home and hanging my rolls to dry from his antique chandelier. It was also really nice to not look at a screen. That’s what appeals to me about hiking and backpacking as well. It's like, setting up your tent or your tarp 200 times and it slowly becomes this automatic thing. You don't even think about it, but it has a reassuring quality to it. I’ve always liked how film keeps us more present while also providing that hands-on sense of craft.

JR: You use a high key contrast and a lot of grain in your pictures, which perhaps connects back to that visceral quality you were talking about earlier…

GD: Yeah, for a while it took a lot of experimentation and post production work to get where I wanted the work to be––which emerges from that idea of doing something hundreds or thousands of times. Slowly I found the sweet spot where I knew, “this is the look,” and could reproduce it over and over.

I've been able to jump back and forth between film and digital because I didn't ever feel a huge difference in terms of the final look of the pictures. I would do my film scans and digital retouching in ways that always matched the overall look of the project, and I never felt like you could look at it and be like, “Oh, this was a film photo and this one was a digital photo.” The real differences is how it has affected my actual photographing and interactions.

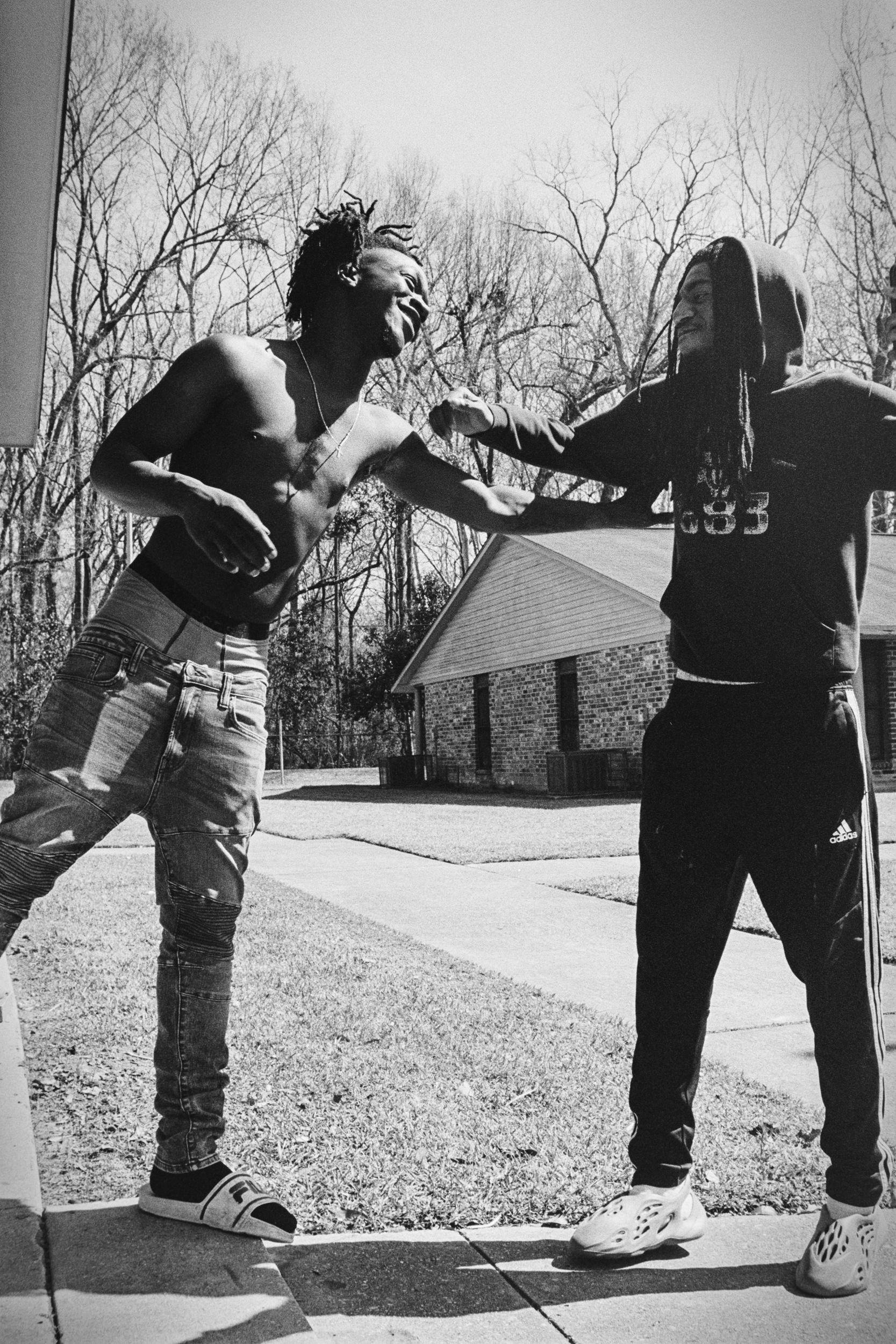

Nook and Nino. Baker, Louisiana.

JR: For me one of the biggest advantages to shooting digitally is how I can immediately show people how they look in the pictures. It builds immediate rapport. Has using film vs. digital impacted how you interact with the people you’re photographing?

GD: Yeah, that was one thing I wasn't super enthusiastic about regarding film. I always share images with the people I photograph, but it's tough when you're shooting 35 millimeter and then have to explain that the film has to be processed and scanned before they can see it. It's not like the people I was photographing were upset about that, but I like seeing people get excited and creating that immediate, sort of collaborative exchange when you can show them the back of the camera. It’s a great way to build a relationship and trust, and there’s been so many times that exchange has been crucial––someone gives me their number and I text them the next day with the pictures and it starts something longer term. With film it's tougher to pull that off, so I'm definitely going to keep going back and forth between the two.

JR: So, what's next with the with the project?

GD: I've been back several times to photograph more since receiving the FPA, but I’m feeling pretty happy about where the project is––it's a pretty full expression. I would really like to publish it as a book, but I’m not making much progress towards that since I’m out here walking across the country…

Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Plank Road. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Jackson, Louisiana.

Delta laughing on the porch. Jackson, Louisiana.

JR: Or maybe you are!?!

GD: Or, yeah, maybe this is what exactly what needs to happen. I still have another probably six weeks of walking to think things through.

JR: As you're walking and maybe thinking about the publication––what do you hope for the book?

GD: There's this amazing musical community in Louisiana; truly one of a kind, world class music is being produced there. But most people outside of Louisiana aren't aware of it.

I pitched the project to National Geographic as an untold story about the grassroots rap scene in Baton Rouge and how it connects to daily life and broader social issues. The story was published in June 2022. Having a big platform as well as a lengthy text component to contextualize the pictures was great, especially in terms of promoting the community to a wide audience. That’s always been the goal.

The book is really more of a prolonged and personal expression. What I would like it to do is summarize this special period of creativity and the way of looking at the world these musicians, my friends, have inspired.